Ironbark - Victoria Hill Historic Mine Reserve Diggings

Gold was discovered on Victoria Hill in 1854 and by 1861, 1,200,000 ounces of gold had been extracted from the site. The first claim was bought for 80 pounds by Prussian immigrant Christopher Ballerstedt and his son Theodore. Christopher Ballerstedt was nicknamed the "Father of the Hill" and was the first to prove that gold reefs extended below the surface. His 200-foot plus mine shafts yielded quartz rich with gold, inspired other miners, and were instrumental in Bendigo becoming the world's deepest and richest goldfield.

It is the site of Victoria's deepest gold mine at 4613 feet (1406 metres). The site still features relics of nineteenth century mining including quartz crushing machinery and the foundations of George Lansell's 180 mine. These features are characteristic of Bendigo's mining history and represent two prominent nineteenth century miners; Christopher Ballerstedt and George Lansell who held important roles in the development of Bendigo.

Victoria Hill Quartz Gold Mines are registered as a site of significance. The site is of historical, archaeological and scientific importance to Victoria. The mines represent the symbolic heart of Bendigo's gold mining history and the importance that mining played in wealth creation and the development of Victoria.

The diggings reserve is accessed from the rear of Albert Richardson Reserve located on Marong Road. The site has steep and unformed paths and is closed to the public at dusk. It is important to stay to the paths to avoid the diggings. Interpretive signs help visitors to appreciate the importance of the site and the remaining relics of Bendigo's mining history.

Opening Hours:

9.00am - Sunset (Daylight Savings Time)

9.00am - 5.00pm (Eastern Standard Time)

Review:

This fantastic site is a real gem where you can explore many elements of this gold mining reserve which was the site of Victoria's deepest gold mine (4,613 ft (1,406m).

Along Marong Road in the Albert Richardson Reserve, just outside the reserve, is the Bendigo Bushfire Memorial, a grassy area with toilets, water tap, shelter with table and BBQs and four more tables, some of which are shaded by trees.

Steps lead up to the top of the hill where a Poppet Head stands with a miners cage. You can take the steps up to the top of the Poppet Head which has commanding views across the reserve and Bendigo.

There are tracks winding throughout the reserve between mullock heaps but make sure you follow all the tracks so you don't miss out on anything. If you need a rest at any time, there are plenty of seats.

Information Signs at Victoria Hill Historic Mine Reserve Diggings

There is a lot of informative signage throughout the Mining Reserve which display the following text:

Welcome to Victoria Hill

Victoria Hill was one of the richest areas on the Bendigo Goldfield. It had many successful mines, including Lansell's '180' and the Victoria Quartz, once the deepest gold mine in the world.

Today, on a walk through the site, you can see the remains of several phases of mining activity - from an open-cut mine of the 1850s to a quartz-crushing battery used in the 1930s. There are also mullock heaps, a poppet head, and the foundations of massive winding engines. On-site signs explain these features.

As you walk through the site, think about the thousands of miners who, over a period of 80 years, worked the rich reefs beneath Victoria Hill.

Bendigo: Shaped by Gold

A city grew around the shafts and stamp batteries of the goldfield. Bendigo proclaimed itself a municipality in April 1855, a borough in 1863 and a city in 1871. During this period, the rough and ready township of the gold rush era was transformed into a city of broad streets and grand buildings. Bendigo was dubbed 'Quartzopolis' in recognition of the relationship between the growth of Bendigo and the development of its mines. Today this wealth is reflected in the grandeur of the city's public buildings and its gardens, statues and foundations.

The Bendigo goldfield

Bendigo was one of the world's richest goldfields. Between 1857 and 1954, 829 mining companies produced up to 22 million ounces of gold. This represented a quarter of all gold mined in Victoria in that period and about one-tenth of the total yield from within Australia.

The rich New Chum Reef passed through the centre of Victoria Hill. In 1871, the Bendigo Goldfield Registry described the area as 'far-famed and world-renowned Victoria Hill' the 'backbone' of the township of Bendigo.

Discovering gold at Bendigo

In 1851, Bendigo was part of an extensive squatting run known as Ravenswood. News of the discovery of gold at Ballarat and Castlemaine reached Ravenswood in the winter of 1851.

No doubt, gold was the topic of much conversation in the shepherd's hut near Bendigo Creek. 'Happy' Jack Kennedy, the overseer on the Ravenswood run, his wife Margaret and a resident shepherd soon found payable gold.

Gold diggers

By Christmas 1851, there were 600 diggers at Golden Point, the site of Bendigo's first gold rush. When this area was worked out, the diggers rushed the surrounding gullies - Peg Leg, Adelaide, New Chum, California - and by the winter of 1852, they had pushed the field northwards to the Whipstick Forest and Eastwards to Epsom.

During this period, gold was won by washing shallow (or alluvial) gravels and clays. News of rich finds brought thousands of hopeful immigrants to Victoria's goldfields. Bendigo attracted more than its share:

Men of almost every nationally, men of position and means mixed with adventures, honest toilers, worshippers, all bent on the same object - the accumulation of the precious metal.

By 1854, these diggers had won over 1.1 million ounces of gold.

Quartz mining

From 1853, some miners turned their attention to the huge outcrops of gold-bearing quartz which promised wealth to those with strength and determination.

Using hammers or picks to smash the gold free of the quartz, they soon recognised the potential of Bendigo's reefs. By 1865, reefing, as it was called, had replaced alluvial mining as the main focus of activity on the goldfield.

Victoria Hill

Between 1853 and 1861, sixteen claims were established on Victoria Hill. One miner wrote of the excitement in Bendigo as these claims tapped new richer reefs:

Victoria Hill is passing belief and inviting incredulity; it is like an eastern tale, within so small an area there should have been extracted a plethora of wealth beyond the dreams of avarice.

To learn more about the history of Victoria Hill and the miners who worked the rich gold-bearing reefs, follow the path to Christopher Ballerstedt's open-cut mine.

Ballerstedt's open-cut mine (1854 - 1871)

You are about to walk through Ballerstedt's open-cut mine. German-born and a veteran of the Battle of Waterloo and the Californian gold rushes, Christopher Ballerstedt bought his claim from two black Americans in 1854 for 80 pounds.

After working the reef in this open-cut mine, Ballerstedt and his son Theodore sank a shaft and at 300 feet (90 metres), struck a rich reef. He celebrated his success with a champagne luncheon in 1857 attended by the Governor of Victoria, Sir Henry Barkly. He swore that his mine would yield a ton of gold, and by 1860, he found gold worth 243,000 pounds.

When he died in 1869, Ballerstedt was known as the 'Father of Quartz Reefing' for debunking the theory that gold would diminish at depth. His successful exploration encouraged others to explore the region's deep reefs.

As you walk through the open-cut, look for the white or brown lines of quartz in the pink, brown or grey sedimentary rock. The quartz contained rich deposits of gold.

Rae's 'Bon Accord' mine (1858 - 1877)

This is the site of William Rae's open-cut mine, named the Bon Accord. Rae purchased three claims in this area in 1858 and crushed his own quartz at a steam-powered battery of six stampers. By 1871, he owned a battery with thirty five stampers. In 1877, Rae's Bon Accord' was merged with the Victoria Reef Co. to form the Victoria Quartz Co.

Originally this area was part of a large outcrop of gold-bearing quartz. The gold was smashed free of the quartz using hammers and picks. Over time, the reefs were quarried or open cut and then the shafts were sunk to follow the reefs at greater depths. You can see some of these shafts in the open cut and the veins of quartz which contained rich depos-its of gold.

William Rae was born in Scotland in 1823. With his two brothers, he immigrated to Australia in 1852, and after a brief stay in Melbourne he travelled to the diggings at Bendigo. Like other miners, he soon turned his attention to the large outcrops of gold-bearing quartz around Victoria Hill. His three claims earned him 30,000 pounds.

William rose to a position of influence in Bendigo a prominent member of St. Andrews Presbyterian Church, a foundation member of the Bendigo Art Gallery and an avid collector of rare books. Respected in mining circles, he often lent money to struggling miners. He died in 1887.

Victoria Quartz Co Mine (1877 - 1913)

At the turn of the century, this was the site of one of the premier mines on the Bendigo goldfield. In 1908, it boasted the world's deepest shaft - 4,478 feet (1,365 metres). The shaft reached a depth of 4,613 feet (1,406 metres) in 1910.

In 1857, eight small claims in this area had been merged to form the Victoria Reef Quartz Mining Co. Another merger in 1877 led to the formation of the Victoria Quartz Co.

For the next three decades, the mine produced consistent profits. In 1910, water burst into the claim, flooding the shaft and halting operations. The company baled water for six months then handed the mine over to the tributers who worked the upper levels for the share of the profits.

The mine closed in 1913, having produced over 48,000 ounces of gold and paid dividends of 99,600 pounds.

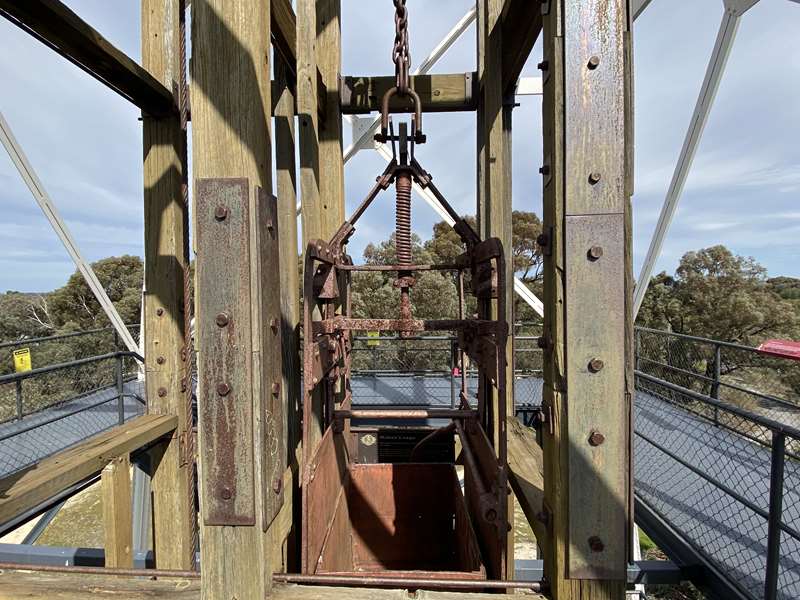

The Poppet Head

The poppet head is the fourth to be erected on this site, marking the site of the Victoria Quartz Company Mine (1877-1913).

Between 1900 and 1920, this poppet head stood at Koch's Pioneer Mine in Bendigo. During the 1920s, it was re-erected at Mt Buninyong near Ballarat and was used as a fire observation and telecommunications tower. In 1955, it was re-erected here at Victoria Hill.

Poppet heads were used to haul men and equipment up and down the shaft. The shaft was divided into three compartments, one for the miners cage, another for the baling tanks and a third, known as the ladder shaft, was for communication and ventilation.

Miner's Cage

Men and equipment were hauled up and down the shaft in cages. Four men or one ore truck could be sent down the shaft at a rate of 25 metres per second. Look for the key-shaped 'butterfly' hook which prevented over-winding and spring catches on the side of the cage. If the cable broke, it would dig into the wooden skids bolted onto the side of the shaft.

Bendigo Quartz Reefs

Quartz reefs were more extensive at Bendigo than at any other goldfield in eastern Australia. A strip of land eight kilometers long and two kilometers wide is dissected by eighteen main lines of reef. This poppet head marks the New Chum line of reef; The poppet head to the south-west 's on the Nell Gwynne Reef.

Baling Tank

Baling tanks like this one were used to 'de-water' shafts throughout the Bench goldfield. Underground water was a major problem at Bendigo. Many shafts were connected by cross-cuts and drives, and as some mines closed, others were left to drain all the underground workings. In 1909, two mines, Lansells '180' and the Victoria Quartz baled over 300 million litres of water.

Quartz Mining

Bendigo's gold was locked in quart reefs below the earth's surface. Miners dug shafts and tunnels to reach the reefs.

At first they used hand-tools, then rock drills powered by compressed air to bore holes into the rock. These holes were rammed with explosives. After blasting, the rock was hauled to the surface. The worthless rock (or mullock) was dumped in massive heaps near the mine; the gold-bearing rock was taken to a crusher or stamp battery.

The miners removed about 5,400 tons of rock for every 500 feet (152 metres) of tunnel or shaft. Mining at that depth needed sophisticated equipment: baling tanks to remove underground water from the shafts and powerful winding machinery to haul the gold-bearing rock to the surface.

Below ground conditions were harsh and sometimes dangerous. Sanitary facilities were primitive or non-existent. Water seeped through cracks in the rock making conditions incredibly humid. Miners worked a ten-hour shift in the air that was thick with the fumes of candles, the smell of human bodies, and the haze of smoke and dust from blasting and drilling.

Poor ventilation and unsanitary conditions contributed to the spread of tuberculosis and phthisis (miners complaint). During the 1880s, deaths from respiratory conditions were 50 per cent higher in Bendigo than elsewhere in Victoria.

Foundations of the air compressor

All that remains of the Victoria Quartz Co.'s engine house are the brick foundations of the steam-driven air compressors. Compressors supplied compressed air to the rock drills used underground by miners from the 1870s onwards.

Crushing the Ore

During the 1870s, gold-bearing quartz was transported through the tramway cutting (to your left) on its way to the crushing battery. Before the development of mechanised crushing, a variety of techniques were used to separate gold from quartz. Many miners 'calcined' or roasted the quartz to make the stone easier to crush. Initially, this was done in the open air, the quartz being staked with firewood, roasted, then crushed with hammers.

Along the path you will pass the mullock heaps of the Great Central Victoria Co. mine. Further along is the Advance open cut mine. As you go, think about the many ways in which mining has changed the landscape.

Lansell's '180' Mine (1861 - 1907)

These brick and granite foundations, originally housed inside a two-storey timber engine house, supported massive winding drums which hauled men and equipment up and down the mine shaft. Look for the smooth mark worn into the brickwork by the winding drum.

George Lansell purchased this mine from Theodore Ballerstedt for 30,000 pounds in 1871. He called his claim the '180' because it occupied 180 yards on the rich New Chum Reef. Between 1888 and 1899, the mine was reputed to have won gold to the value of 1,000,000 pounds.

In 1895, the shaft was down to 3,179 feet (968 metres), the deepest mine in Australia. When it closed to 1907, the mine yielded over 77,000 ounces of gold.

Great Central Victorian Mine Co. (1871 - 1907)

These are the brick foundations of the winding engines of the Great Central Victorian Mine Co. The poppet head shaft was about 15 metres to your left. The shaft reached a depth of 2,845 feet (867 metres).

The Mine operated on this site between 1871 and 1907. Notice the proximity of this mine to the Victoria Quartz Mine Co. Mine.

A multi-cultural field

Although the majority of miners came from Britain, the Bendigo goldfield attracted people from all nations. Places like California Gully, New Zealand Gully and Chinaman's Flat describe some of the nations represented on the field.

At Victoria Hill, Germans and black Americans, veterans of the Californian gold rushes and miners from the Cornish copper fields came together to search the rich lodes.

Cornish miners were experts in deep mining. They were drawn to Bendigo where the gold ran deep and experienced miners were assured of constant employment.

Advance and Adventure open-cut mine

This is the site of the Advance and Adventure open cut, which was mined during the 1850s and 1860s. To your left you can see the three sides of a mining shaft incorporated into the open cut. Imagine the physical effort required to dig this shaft using a pick and shovel.

Revival

During the depression of the 1930s, the price of gold almost doubled. This and the high rate of unemployment led to a revival of mining throughout Victoria. In 1934-35, the Bendigo goldfield produced a third of Victoria's total yield.

Between 1933 and 1949, this twenty-head battery crushed quartz for several companies including the Little 180 Mine, the New Chum Syncline and the Bendigo Crushing Company. It was manufactured by Thompson's of Castlemaine in 1933.

The stamps were lifted and dropped, pulverising the quartz into sand-sized particles. After crushing, the sand passed over a series of tables - a mercury-coated plate table that amalgamated the gold and ripple-board tables that trapped most of the gold or heavy minerals. A mine could operate successfully if it produced one third of an ounce of gold for every tonne of quartz brought to the crusher.

In 1949 the battery fell silent, ending 30 years of mining on Victoria Hill. Over the next decade, rising wages, falling profits, and a shortage of skilled labour and materials tested the last of Bendigo's mining companies. The closure of the North Deborah in 1954 saw the end of 101 years of continuous quartz mining on the Bendigo goldfield.

Environmental change and land reclamation

Prior to 1852, Victoria Hill supported a dense forest of Ironbark trees and the surrounding plains featured green grass, shady gum trees and clear flowing creeks.

Miners tested the outcrops of gold-bearing quartz and discovered fabulous riches. Thousands of prospectors rushed into the valley of Bendigo and mining activity quickly degraded the landscape. The Ironbark forests on Victoria Hill were soon transformed as miners plundered the quartz reefs for gold. A new landscape of mullock heaps and poppet heads replaced the forests and grassland.

After the mines closed, the legacy of mining activity continued to affect life in Bendigo, particularly for residents living close to the massive tailings dumps. In those days, there were so many mining dumps around Bendigo that every time the wind blew, nearly every house and shop in Bendigo would be full with grey sand.

From the 1930's onwards, the Mines Department began to cover abandoned nine shafts in the Bendigo district. Work commenced in the populated area around Bendigo and Eaglehawk, with particular emphasis on securing abandoned shafts near schools. By the 1960s, most shafts in the Bendigo area had been made safe.

It is important to note that, even today there can be movement in the mine shafts. Please stay on the paths and take care.

Albert Richardson Reserve Bendigo Bushfire Memorial

The beautifully designed memorial wall features a memorial remembering the catastrophic Black Saturday fires in Bendigo on 7 February 2009. It displays the following text:

On Saturday, 7 February, 2009, Victoria experienced an unprecedented and catastrophic event as firestorms raged through much of the state. For many, this day will forever be remembered as Black Saturday.

In Bendigo, the Bracewell Street fire, as it came to be known, swept quickly and with little warning through the north-west of the city. Powered by wind gusts of up to 80 kilometres per hour and temperatures into the mid-40s Celsius, the fire took the life of one resident, along with numerous pets and wildlife. It destroyed 58 homes, countless sheds and outbuildings, cars, boats and caravans.

In a few short hours it devastated an area of almost 500 hectares, threatening to spread to the city's CBD, and changed the lives of so many residents forever.

Less than two kilometres north-west of this site, Bendigo resident Mick Kane tragically lost his life - fighting, like so many others - to save the home and family he loved under impossible circumstances. Many residents were forced to flee for their lives or watch their precious homes and possessions burn.

Bendigo remembers all those whose lives were so devastated on Black Saturday, and who fought back with immense courage and optimism in the face of adversity.

In the face of unprecedented disaster, Bendigo banded together like no other time in its history. This memorial acknowledges the bravery and ingenuity of our emergency service workers, including our firefighters, police and ambulance service; the local residents who banded together in horrific circumstances, not only to fight the fire, but support one another in so many ways; the many relief and aid organisations, recovery agencies, counsellors, businesses, media outlets and caring citizens who gave so generously in the days, weeks, months and years following Black Saturday.

Photos:

Location

40-56 Marong Road, Ironbark 3550 View Map