Foster - Pearl Park

Pearl Park is a delightful park which runs between Main Street (opposite the Museum) and the local creek. It is ideal for picnics, barbecues and relaxing and has a number of interesting historic signs and sculptures.

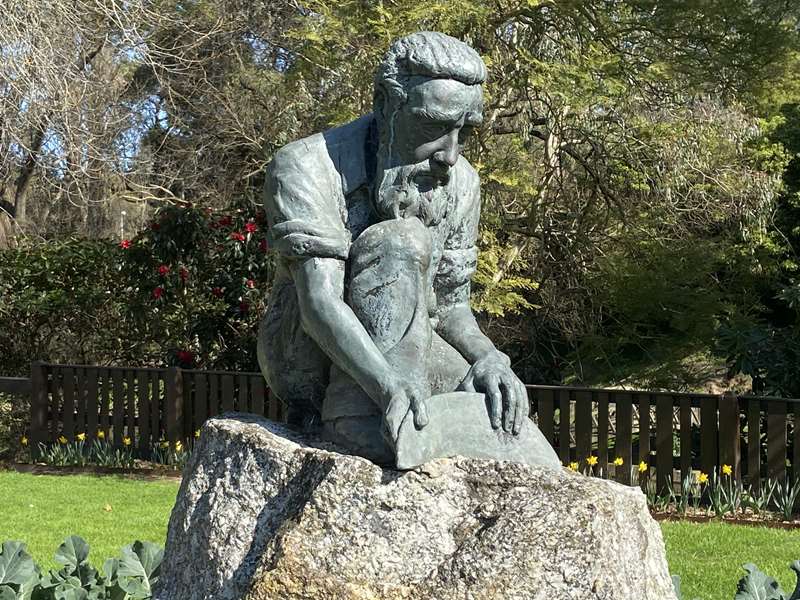

There is a sculpture of a miner panning for gold which is in commemoration of the discovery of gold near this site by Daniel Graham, Griffith Griffith, James Northey, James Palmer and Alfred Sparkes early in 1870.

One of the signs provides a detailed history of Lewis Hubert Lasseter, later known as Harold Bell Lasseter, who moved to Toora during World War I. He had a number of innovative ideas for the area but his fame rests on his belief that there were vast gold reserves west of Alice Springs. In 1930 he headed out from Alice Springs to find "Lasseters Reef" and died in the heat of Central Australia's summer in February, 1931. The local sign calls him "Our Eternal Optimist".

Along Main Street there are toilets, three unshaded tables, shelter with two tables, a seat, BBQs and water tap.

The historical information signs are:

The Golden History of Stockyard Creek

South Gippsland's great blackwood, mountain ash and bluegum forests are inextricably linked with the discovery of gold at Stockyard Creek, or Foster as it was later named.

In 1968 James Northey of Bairnsdale and his mate James Palmer were combining splitting blackwoods for barrel staves with fossicking for gold in the creeks between Hoddle and Welshpool. On Boxing Day in 1869, the pair found a little gold near the mouth of Stockyard Creek, enough to encourage them to stay in the locality to look for more.

Northey and Palmer were joined soon after by Alfred Sparkes, Griffith Griffith and Daniel Graham, and together the five men felled trees while continuing their search for gold. They were supplied with fresh food grown by an early Franklin River farmer, John Amey, who in return was promised a share of any gold discoveries made.

In late 1870, a quantity of staves washed up on a beach near Port Albert prompted a Crown Lands official visiting the Corner Inlet district to investigate their source and was told that a schooner carrying timber to Melbourne from splitters working at Stockyard Creek, had been wrecked on Rabbit Island.

As none of the five men held Government licences to split timber, Amey, whose son-in-law was the local police constable accompanying the official, sent them a warning. They quickly hid their axes, saws and wedges and moved further up Stockyard Creek towards the heavily timbered foothills of the Strzelecki Ranges, acting as prospectors. The men soon came to a place where the gully widened and a low limestone shelf created a natural pool. They decided to set up camp and Northey, after throwing in a line to catch a fish for the midday meal, dug an exploratory hole a few paces downstream. At a depth of 'about three feet' his shovel brought up dirt flecked with colour, which when washed yielded about forty grains of gold.

Northey called the others and then, until darkness made more work impossible, the five men searched, finding gold everywhere, in and along the creek. In the morning one of the party walked to Amey's farm with the news, and he hurried to see for himself. That day they also came across gold concentrated in the western bank of the creek. The six men decided to peg two claims, Northey, Palmer and Graham would share a creek prospecting claim, while Sparkes, Griffiths and Amey would make a bank sluicing claim.

They also offered a share to John Richards, an experienced Cornish miner who was prospecting in the area, if he would help them sink shafts and drive tunnels. In March 1870, Griffiths and Richards took the gold they had found to the Port Albert branch of the Bank of Victoria where the nuggets were put on display, effectively beginning the Stockyard Creek gold rush.

Griffith stayed at Port Albert to buy mining equipment while Richards rode to the neatest mining registrar at Russells Creek, now known as Tanjil, to register the claims The six men formed a partnership and the two claims were amalgamated into one named the Great Uncertainty which proved to be very rich indeed. The wet winter of 1870 postponed the rush but by early 1871 there were more than two hundred miners working along Stockyard Creek. During the next eight years three tonnes of gold were found in the district.

With Pan, Pick & Shovel

By early 1871, more than two hundred miners were shallow working Stockyard Creek, suing shovels, dredges, cradles, pans and sluices, altering its natural course several times as they dug. The nearby Ophir, Kaffir and New Zealand Hills, Whipstick and Cody Gullies also proved to be rich in easily accessible gold.

In March 1871, miner on the Pioneer claim found their first large gold specimen weighing almost half a kilogram, the Old Mann claim on Ophir Hill returned two nuggests 1.81kg and 1.9kg respectively.

In 1874 Edwards Hayes and eleven others, nicknamed the 'twelve Apostles', leased the middle section of the Prospectors claim and called it the Tributers, which proved to be very lucrative as did the Prussians, Scotchmans, Big Log and Rise and Shine claims. The Madame Henty claim was one of the deepest of Stockyard Creek's alluvial workings, reaching nineteen metres by the time it closed in 1890.

The Number One South claim struck gold-bearing quartz after all of its alluvial gold was worked out aqnd was the first mine to crush stone on the goldfield. A newspaper report of the period stated that Stockyard Creek had 'every appearance of a splendid goldfield in view'.

This encouraged even more prospectors to take the paddle steamer Murray from Queens Wharf in Melbourne around Wilsons Promontory to Port Albert, where many bought their mining equipment and provisions from newly entrepreneurial storekeepers. The screw-steamer Tarra then carried them across Corner Inlet to the Stockyard Creek landing about five miles south-east of the diggings and its evolving township of tents, slab huts and timber houses. This village was later renamed Foster in honour of the Gippsland gold warden and magistrate.

Miners walked and rode through either summer dust or knee-deep mud to Stockyard Creek via a bridle path, or were driven along a bullock-dray track that later became the route of the horse drawn tramway with rails of bluegum.

By 1876 the Bank of Victoria had bought more than 1134kg of alluvial gold from miners in the district.

During the early years local police escorts left town before dawn, leading packhorses laden with gold-filled boxes, on their way to Shady Creek, Welshpool, to meet police from Port Albert. The gold was taken to Port Albert and placed on board the Murray bound for Melbourne.

At the height of the Stockyard Creek gold rush, up to ten police officers at a time were sent from Melbourne to escort the gold to the Landing and to oversee its loading onto the Terra. The gold was then transferred to the Murray off Rabbit Island in Corner Inlet, to further reduce the likelihood of robbery.

In 1888 the Victory Goldmining Company sank a shaft under Kaffir Hill and struck quartz veins rich in gold between twelve and twenty-five metres, reviving the golden era of Stockyard Creek for a further twenty years of reef mining.

Lasseter Our Eternal Optimist

Lewis Hubert Lasseter was born in 1880 at Bamganie, between Geelong and Ballarat, in Victoria. After a colourful childhood and adolescence he sailed overseas, first to Europe and then to U.S.A. Marrying at Niagara Falls in 1903, he returned to farm in northern New South Wales in 1908.

For a short period he served in the A.I.F. during World War 1, but before peace was declared he was discharged, and moved with his family to Toora, Victoria. In 1918 after the loss of millions of tonnes of shipping to submarine activity, Lasseter became convinced that it was practical to build wooden ships of up to 2,000 tonnes at nearby Port Welshpool, and began campaigning to set up a shipyard there. Timber mills were planned in the forest and other support needs investigated.

Lasseter travelled the district selling the idea enthusiastically, but it was too close to the end of the war and when peace did come it brought cancellation of ship-building contracts across the country, and the scheme fell through.

Believing the district had great potential, Lasseter switched from ships to creating an industrial complex rivalling Newcastle, a place where returned soldiers could be settled and gainfully employed. He visualized numerous manufacturing enterprises, the Agnes River and brown coal from nearby Gelliondale powering electrolytic and chemical works, leather goods, spinning and waving of woollens and the production of alcohol from bracken, brown paper, pottery, china, concrete pipes and glassware would also be produced.

In September 1919 the State Government notified Lasseter that his plan was rejected on the grounds that the proposed site of his township was too remote. He was not to know that the very same area at Barry Beach would be taken up by Esso-BHP in 1997 as a construction yard for the huge Bass Strait oil rigs.

While living at Toora and Foster during 1919-1920, Lasseter worked for the local Port Authority erecting timber beacons in Corner Inlet. Suitable saplings were felled, floated down the Franklin River and loaded onto his boat, Victory, which is displayed in the museum. It is not known how he raised the heavy timbers into position but it was done.

He had changed his name to Harold Bell Lasseter and as 'Harry,' was an Australian battler, always poor but always ready to tackle anything. He built houses and boats, worked as a tradesman on Parliament House in the infant Canberra, and was an artisan in a Sydney pottery.

He wrote numerous articles to newspapers on a broad range of social issues end proposed practical ways shortening the war. He submitted a design for the Sydney Harbour Bridge, little different from the winning entry. He commented upon the dangers of drink-driving and suggested a remedy for the problem. He also put forth the idea of multi-storey parking for 10,000 cars in the centre of Sydney, these in the 1930's.

His writings were seriously pro-Australian. He disliked Britain, distrusted British rule and foresaw the day Australians would sever the political ties and become self-governing. He predicted the Japanese attack on Australia and argued that Townsville should be a major naval base, sixteen years before World War 2 began.

All his life Harry Lasseter was interested in gold, fossicking for it whenever he could, his daughters played with nuggets in their homes at Toora and Foster. The interest grew to obsession by 1929, and he succeeded in persuading businessmen to back a search for what became known as Lasseter's reef in Central Australia.

On the 21st July 1930 he struck out from Alice Springs with a well equipped expedition of trucks and aircraft. Dissension in the party spread and by September the search was abandoned by all except Lasseter who pushed on into country west of Ayers Rock (Uluru). There had been a drought for seven years and in the shrivelling heat of February 1931, out of food and water, Harry Lasseter perished,

His reef has never been found.

The words of Theodore Roosevelt became his epitaph and applied to the hundreds of miners who were fired by gold fever here in Foster.

It is not the critic who counts, or how the strong man stumbled and fell,

Or where the doer of deeds could have done better

The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena,

Who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotion,

And spends himself in a worthy cause.

If he fails, at least he fails while daring greatly so that he will never

Be one of those cold and timid souls who knew neither victory or defeat.

Across the road, east of the Museum, is another sign:

Digging Deeper

By 1871, the concentrated working of the creek and adjacent valleys encouraged miners to dig deeper. First good results were found down to twelve metres, but more extensive explorations resulted in shafts such as the Victory being put down to a little short of one hundred and fifty metres. Amalgamation took place between it and surrounding mines. Rich colour was obtained from a gold-bearing quartz reef discovered running north-south beneath the village in mid 1871.

In addition to the Victory complex, there were shafts on Kaffir Hill (immediately east of the Main Street) on New Zealand Hill further east again, and Ophir Hill, north-east of the township.

Among the men working Whipstick Gully was Paddy Hannan, the future discoverer of the Golden Mile, the fabled goldfield at Kalgoorlie In Western Australia, reputed to be the richest in the world.

By 1872, Stockyard Creek had been given the new name of Foster and with seven hundred inhabitants, accommodation was in short supply. The area had been surveyed and a town plan produced. There were seventeen hotels, a bakery and a restaurant, some eating houses boasting they could provide seventy meals at once. The descendant of the first Exchange Hotel stands on the original site today.

Many substantial shafts were sunk into the quartz reef which was extensively worked in the area between the present Exchange Hotel in the south, to a northern limit of McDonald Street, with most activity centred on and around Kaffir Hill. The Gladstone, Golden Bar, Jubilee and Prussians went to depths between thirty and sixty metres, all producing encouraging results from some veins that were up to ten centimetres thick. One example from the Great Southern Railway Company weighing eleven kilograms, was studded with rough gold, the best specimen seen in Foster for years.'

Most mining was becoming less profitable by 1878, little or no alluvial claims being worked. There was still optimism about rich leads found in the quartz reefs but the great hopes held for a goldfield of promise were dying.

For its first twenty years. the Victory mine was worked as a private venture, but in 1890, when trial crushings improved, it was decided to upgrade pumping gear and other heavy equipment and the mine was floated into a public company.

Working twenty-four hours, seven days a week for many years, that mine had the longest life of all those at Foster.

In 1908, the Victory's shafts were sealed. Falling prices and the inability of the pumps to contain an increasing water problem brought its closure, and the golden dream at Stockyard Creek was over.

Photos:

Location

8 Main Street, Foster 3960 View Map