Chewton - Welsh Village Walk

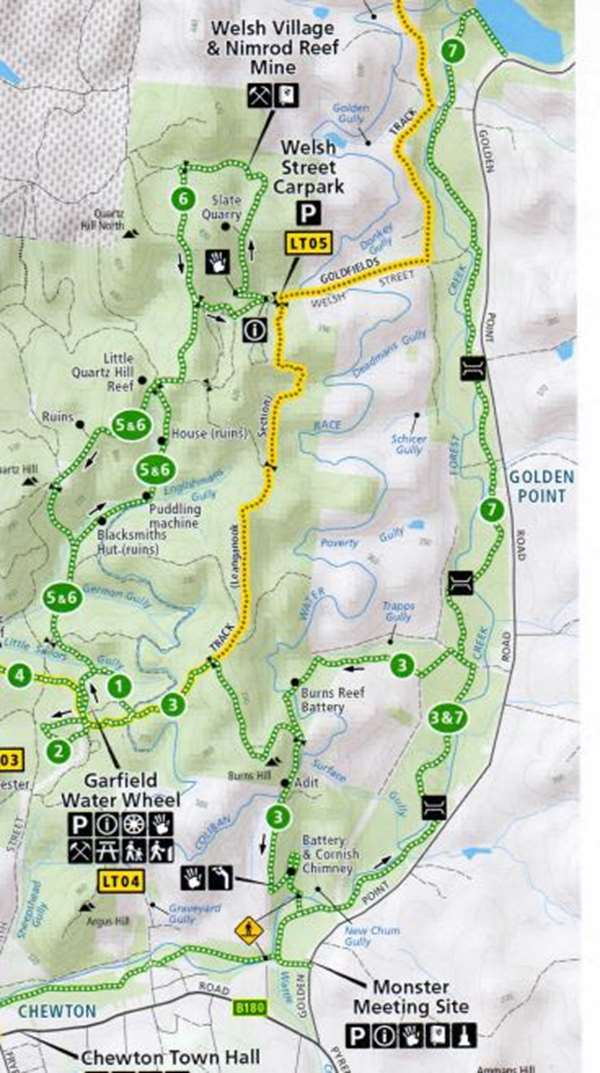

Welsh Village Walk is a grade 3, 5km loop walk which takes 2-2.5hrs on a gravel and earth track. There is uneven ground and moderate hills with a few steep sections. The track is unclear and not signed through Nimrod Reef Mine and Welsh Village. Bushwalking experience and a moderate level of fitness recommended.

Alternatively from Welsh St carpark / Goldfields Track stop LT5 the walk is 1.2km loop (45mins).

Step back in time amid the atmospheric ruins of Welsh Village, an abandoned goldrush settlement, and learn about Dja Dja Wurrung history before and during the goldrush. The full walk starts by following the same route as the (4) Quartz Hill Walk. It can also be walked as a shorter loop or detour from the Goldfields Track (stop LT5) starting from the Welsh St carpark.

From the Garfield Water Wheel Trailhead: follow the (5) Quartz Hill Walk, until you reach the turn off for the (6) Welsh Village Walk. Turn north-east (right) along Tobys Track and then north onto an unnamed track (follow the signs). Where the track divides, follow the loop to the east (right) towards Welsh St and the car park. Follow the signs from there.

From the Welsh Street carpark / Goldfields Track (stop LT5): leave your bike or vehicle at the carpark on Welsh St and follow the signs to begin the loop part of the walk from there. Dogs and vehicles, including pedal bikes, are prohibited at the Nimrod Reef Mine and Welsh Village and should not be taken beyond the carpark.

Welsh Village Walk Map

The Quartz Hill Walk is labelled (6) on the map.

Look for the interpretive signs located at the car park and further along the walk to learn about the mine and village and Dja Dja Wurrung's cultural connection to the area.

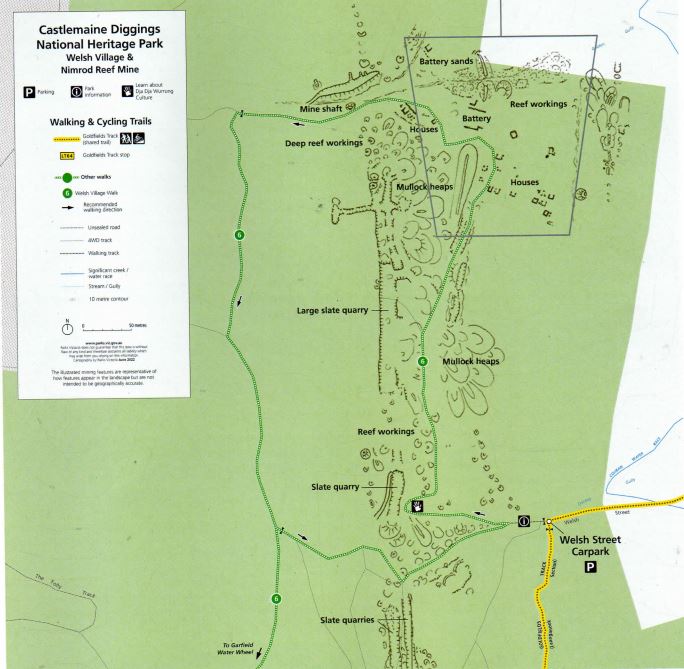

The track is steep in places and may be slippery in wet weather. To the east (right) of the track, there are mullock heaps and glimpses out over Donkey Gully and the Golden Point Flats from between the trees, and to the west (left) is a slate quarry at the crest of the hill. The track is not marked or signed through Nimrod Reef and Welsh Village due to the special historic significance of the site.

Slated for construction

Slate is a hard rock that splits relatively easily into thin slabs, making it a much-sought after building material used for walls, roofs, tiles and paving. It was quarried in Wales as early as the 1100s, with the industry peaking in the 1830s-1870s.

This quarry operated in the 1950s, however, its slate was used long before that, first by the Dja Dja Wurrung People, and then by gold miners. There are several disused quarries in the area, including this one and the one at nearby Specimen Gully. Slate is still mined near Castlemaine.

The seams of slate that run through this area were created millions of years ago, long before the dinosaurs. 480 million years ago, Central Victoria lay beneath a warm shallow sea, teeming with corals and early fishes. The earth's crust was unstable, with tectonic plates on the move.

Over the next 40 million years, plates in the east and the west pushed towards each other, compressing the seabed to half its former width, and the ocean drained away. The folded sand and mud layers were welded together as sandstone and mudstone. Molten rock, rising up through the earth's crust, heated and compressed the mudstone turning it into hard slate.

The cliffs and blocks around you exhibit great diversity of colour, which reflects the different minerals that accumulated in the layers of the mudstone. The dark bands contain more carbon or iron sulfide, red and purple bands contain more hematite (iron oxide), and green bands contains more chlorite.

The large blocks of broken slate at the foot of these impressive cliffs demonstrate why it is not safe to climb them or get too close to the foot of the cliffs.

A golden gully fit for a king

Beyond the slate quarry, the track starts to descend into Golden Gully, passing through the Nimrod Reef Mine. Nimrod Reef (also known as Donkey Reef) lies between Donkey Gully (behind you) and Golden Gully (ahead).

There are many shafts and mullock heaps on both sides of the track, a very large open-cut mine that has been partially filled in by later phases of mining, and an adit (tunnel) dug by Jones and Lewis, who held claims on this reef.

"M'Glenchey and mate" began mining Nimrod Reef in 1854, and after the introduction of the Miner's Right in 1855, which allowed miners to take out mining claims, other parties took up adjoining claims.

It was common for miners on the goldfields to seek out others from their home countries, and documents from this time show a predominance of Welsh surnames: Williams, Morris, Price, Lewis, Jones, Powell, Bowen, Morgan, Evans, Davis and Davies.

The reef at the surface proved very rich, with some parties getting over 9kg of gold from 1,000kg of quartz. By mid-1859, seven steam-driven crushing batteries were in operation, and nine claims were being worked by 49 miners.

However, it wasn't without challenges. From 1861, as the surface gold was exhausted and shafts were dug deeper, water became a persistent problem. With significant investment required in drainage machinery and dwindling returns, work became intermittent.

In 1888, the original co-operative, Crown Nimrod, was bought out by a Melbourne syndicate. Torrential rains brought mining almost to a complete halt in 1889 and by 1896 work had ceased on the main shaft. Efforts continued into the 1900s, but the boom was over.

From the right to build a home, to a community of stone

Descending into Golden Gully, you can see the ruins of several stone cottages and workshops. This settlement, which has become known as 'Welsh Village', was constructed by the miners of Nimrod Reef. It was one of many small settlements with houses, stores and hotels, and sometimes even schools and churches, in the mining locality of Golden Point.

From 1857, the Miner's Right entitled holders to claim a Residential Area - up to a quarter acre of land for a home and garden. Miners searching for shallow alluvial gold rarely stayed in one place for long, but quartz reef mining was a longer-term prospect and offered miners a more settled life.

Miners, including those working at Nimrod Reef, began to claim their Residential Areas and replace canvas tents with homes of wood and stone.

In the earliest days of the goldrush, men often left their families back home, but it wasn't long before women and children became a common sight on the goldfields. If miners had enough money, they sent their children to school (which could be in a tent or under a tree). However, most children had to help with the mining or in the house or garden (collecting wood, carrying water, washing clothes).

Work usually stopped half-an hour before sunset. In the evenings, people sat around the fire or hearth - cooking, talking, reading, singing or playing music on whatever instruments they bought with them or could fashion out of the materials to hand.

A change is as good as a rest

Sunday was strictly maintained as a day of rest from mining but was rarely a rest from anything else. Families repaired equipment, extended their homes, took their weekly bath, and finished off the week's housework.

Laundry was one of the worst tasks. Water had to be collected from the nearest creek or dam. Clothes caked in mud from the diggings had to be soaked, scrubbed, rinsed and wrung out by hand. Women usually did this on a Monday, but a single man had to wash and mend his clothes on his day off.

When the chores were done, people put on their best clothes and went to church, shopped for food or clothes, attended dances and had picnics. Sports like cricket, football, horse-racing, cockfights and boxing were popular. Sunday was also the day that mail arrived at the Forest Creek Post Office, bringing long-awaited letters from home.

Held together by mud and kinship

Most of the buildings were constructed with irregular blocks of local sandstone, held together with mud mortar, sometimes with the addition of smaller stones. Often, stone was only used for the foundations and fireplaces, with the walls and roofs wood and bark.

Bricks were only used in a few buildings, likely after the 1880s. Small quantities of corrugated iron and slate from the nearby quarry were also used. Dry stone walling (without mortar) was used for retaining walls to contain mullock heaps.

Can you see some colour variation in the ruins?

Sandstone with a yellow hue was found near the surface. Sandstone with a grey or blue hue was brought up from below the water table where it was not exposed to the weathering and oxidation that turned it yellow. Buildings with grey or blue stone were likely built after 1868 when mining commenced below the water table.

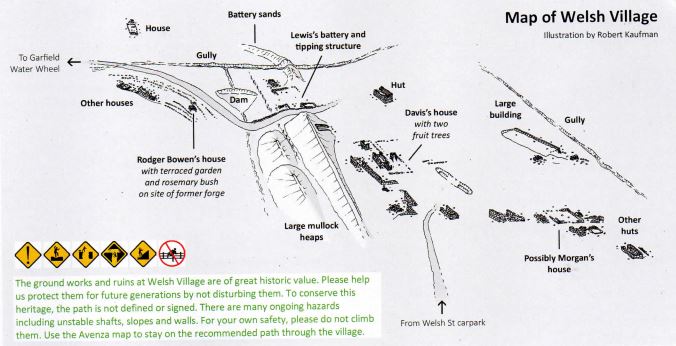

Welsh Village was inhabited by Welsh miners for over fifty years, held together by national and family ties. There is evidence that Thomas Morgan, William Davis and Rodger Bowen were still living there in 1893.

Echoes of another time and place

The Davis family were the last of the original settlers to leave, remaining there until Mrs Davis finally moved to Alexandra in her old age. Look for the ruins of their house with several fruit trees growing in front of it.

Rodger Bowen's house can be identified by its terraced garden beds with a huge rosemary bush. Behind the house a neat, flagged path leads southwards, probably the path used by Rodger Bowen each time he set out to work his shafts.

Visit in spring, and you may also see daffodils - the national flower of Wales - and other European bulbs in flower. Can you recognise any other non-native species? Take a moment to sit quietly among the ruins and reflect on what life was like here in the late 1800s.

What would it have been like to live here?

Most homes were simple, with only one or two rooms, just large enough for the number of beds required, a fireplace for warmth and cooking, and perhaps a table. Light came from the fire, candles stuck in empty bottles, or oil or kerosene lamps. Beds were usually stretchers made from wooden frames and canvas or flourbags, sometimes with a mattress of gum leaves.

The miners used whatever was available. A pair of boots, or flourbags stuffed with clothes might make do as a pillow. Buckets could be turned upside down and used as stools. Trunks or packing cases became tables. People only purchased things they couldn't make themselves, such as wool blankets, or the luxury of a possum skin rug for winter warmth.

Meals were also simple. Billy tea, mutton and damper were the standard fare, and often all that was available, particularly in remote locations like this. General stores at Golden Point or along Forest Creek would have sold a variety of goods, including clothing, tools, household items, candles, kerosene, tobacco, tea, coffee, flour, sugar, salted meat and tinned goods.

Butchers sold freshly slaughtered meat - usually mutton, sometimes beef, and occasionally pork. Other fresh produce (like chicken, eggs, milk, fruit and vegetables) was rare and expensive.

Scurvy, caused by a lack of Vitamin C, and malnutrition were common. Some families planted fruit trees and tried to grow their own food, but land and water were limited. It would have been almost impossible to survive as a vegetarian on the diggings.

The monotony was occasionally broken by hunting wild animals and birds. A possum or cockatoo pie was considered a fine meal after months of nothing but mutton and damper. And the skins and feathers could be put to good use.

Can you imagine what the village was like on a Sunday when the batteries fell silent and families gathered to pray or play sports, perhaps share a meal with friends? Maybe you're playing a tin whistle and watching the children dance, or replying to a letter from your family back in Wales?

Leaving the village, the track climbs in stages (some moderately steep) in an easterly and then southerly direction over Quartz Hill North, before reaching the junction 'where you started the loop through Welsh Village.

If you parked on Welsh Street or took a detour off the Goldfields Track: turn left (east) at here and follow the track back to the carpark (Goldfields Track stop LT5).

To extend your walk: follow the directions above and join the Goldfields Track to Expedition Pass Reservoir (2km, 30min), where you can stop for a swim. Then head south along the (7) Forest Creek Trail and return to Garfield via the (3) Monster Meeting Walk (6.5km, 2hrs).

To return directly to the Garfield Trailhead: continue straight on (south) to the junction where the (5) Quartz Hill Walk and (6) Welsh Village Walk diverge. Here, you can return to the Garfield Trailhead by following either track:

- Continue straight on (south-west) to return via the section of the (5) Quartz Hill Walk that you haven't walked yet: new features to explore, a slightly steeper descent, allow a bit longer.

- Turn south (left) to retrace your steps: a similar distance, but slightly gentler descent, recommended if you are short on time or energy.

Access for Dogs:

Dogs may be walked on a lead on the tracks around the Garfield Water Wheel, including the (5) Quartz Hill Walk. They must be kept on a lead and under control at all times. Please collect and remove your dog's droppings for the sake of other visitors and to avoid stress to native animals.

Please note that the Nimrod Reef Mine and Welsh Village is a designated Special Protection Area due to its historic significance, so the (6) Welsh Village Walk is not marked or signed through that area. Dogs and bikes are prohibited.

Safety:

The Castlemaine Diggings are a heavily mined landscape and contain a variety of ongoing hazards, including uneven and unstable ground, mineshafts, open cuts, quarries, and mine tailings. For your own safety, please stay on mapped tracks and supervise children. Comply with local signs and do not climb over or around barriers and fences or on the stone foundations of the water wheel.

Location

Leanganook Track, Chewton 3451 View Map

Web Links

→ Quartz Hill Walk and Welsh Village Walk Heritage Notes (PDF)