Chewton - Eureka Reef Heritage Walk

The Eureka Reef section of the Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park contains some of the oldest and best-preserved quartz mining relics in Victoria, offering visitors a golden opportunity to explore this extraordinary era in Australia's history. The Eureka Reef Heritage Walk is a 1.8km self-guided walk in relaxing bushland takes you back through 140 years of mining history.

The rush for gold

Gold was discovered in the Castlemaine area in 1851. People from around the world raced to Victoria, hoping to strike it rich. The gold rush, and the social and political changes that it triggered, played a huge part in shaping the multicultural democratic Australia of today.

Relics of the earliest quartz mining operations in the country are found at Eureka. Quartz mining was slower and more complex than digging for alluvial gold, so many miners came with their families and built homes at Eureka. Once there was a village here and the sounds of machines filled the air.

However, the glory days of the gold mines were short-lived and by the 1870s most of the mines had closed. Prospectors have returned to Eureka many times since - including during the economic depressions of the 1890s and 1930s - hoping to discover the gold that their predecessors missed, but without much success.

When the gold was gone there was little to keep people in villages like Eureka. As they left in search of new opportunities, many small mining towns and villages simply faded away, homes and businesses slowly crumbling to rubble. Today, the only sounds you'll hear at Eureka are the birds and the wind in the trees.

Nature's resilience

The forest at Eureka is different now than it was before the gold rush. The Box-Ironbark forests that covered these hillsides then contained fewer but larger old trees. However, the demand for fuel and building materials lead to the forests being stripped bare. The loss of mature trees with nesting hollows, combined with habitat fragmentation and introduced predators has taken a toll on native birds and animals.

Although mining had a detrimental impact on Box-Ironbark forests in the short term, it has also contributed to their protection in the long term. To ensure timber was available for mining needs, areas that might otherwise have been converted to farmland were set aside as forest reserves.

Today, the forests are regenerating, and Eureka is a beautiful place to appreciate both nature's resilience and the extraordinary story of the gold rush. In late winter and early spring, the forest comes alive with wildflowers, and with different species of eucalypts and wattles flowering throughout the year, there is always something to appreciate.

Things to do

There are no toilets at Eureka Reef. The nearest public toilets are in Chewton, behind the Town Hall, or at 23 Lyttleton Street, Castlemaine, approximately 20 minutes away by car.

Picnics

There is a picnic table at the far end of the car park, and a couple of benches scattered along the walk. However, there are no bins, so please take your rubbish home with you.

Birdwatching

Many species of birds can be seen at Eureka, including year-round residents like currawongs and honeyeaters, and migratory species like the endangered Swift Parrot. Bring your binoculars and a bird guide, and look up into the canopy, on the tree trunks, in the grasses and on the ground.

Wildflowers

From late winter through to early summer, the forest floor is full of wildflowers. How many different species can you see? If you don't have a field guide, bring a camera or a sketchbook and see how many you can identify when you get home. The Castlemaine Field Club have a wonderful website that can help you name what you saw castlemaineflora.org.au. Please tread lightly - all plants and flowers in the park are protected, and it is forbidden to remove or disturb them.

Walking

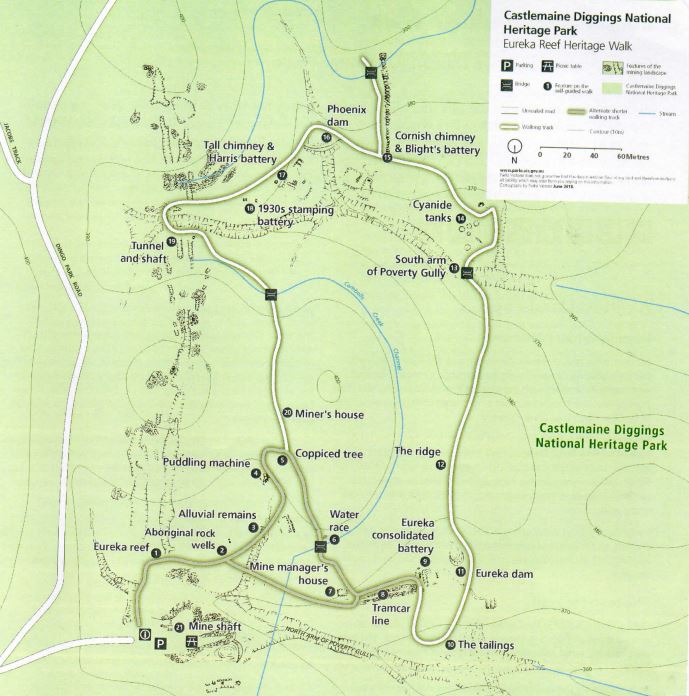

Map of Walk Route

A 1.8km self-guided walk in relaxing bushland takes you back through 140 years of mining history. The walk helps you see the forest through the eyes of the Dja Dja Wurrung people, alluvial gold diggers and quartz reef miners. Numbered posts along the track correspond to the text in this factsheet.

This is a Grade 3 formed track, with a few short steep sections and uneven ground that may be slippery after rain. Suitable for most ages, with moderate fitness levels, including children with close supervision. Dogs are permitted, but must be kept on a leash.

Full loop: 1.8km, stops 1-20, allow 1-1.5 hours.

Shorter loop: 550m, stops 1-9, allow 30-45 minutes.

Exploring the relics

Stop 1

Eureka reef - a golden opportunity

Here you can see the remains of the reef. Before the miners arrived, there was a huge outcrop of white quartz extending in a ridge across the hills. In the 1850s and 1860s, the reef was mined as an open cut. Miners broke up the rock and crushed it to extract the gold.

The exclamation 'Eureka!' comes from Ancient Greek and means 'I found (it)'. It became a familiar cry during the gold rushes of Victoria and California, and was adopted as a name by many places associated with gold mining.

Stop 2

Aboriginal rock wells - water for the Dja Dja Wurrung People

The small depressions in the sandstone here are rock wells. The Djaara (Dja Dja Wurrung People) created them to collect rainwater by enlarging natural holes. They placed rocks over the holes to prevent animals, leaves and debris from polluting the water. Wells like these allowed them to travel long distances, even in dry weather. The Djaara refer to mining landscapes like Eureka as 'upside down country'.

Stop 3

Alluvial remains gold in the grass

In 1854, and again in the 1870s, diggers came here looking for alluvial gold that had slowly eroded and washed off the reef into the soil, grass and creeks. They washed the topsoil in cradles, pans and puddling machines to separate the gold from the soil. Before long they'd stripped the hillsides, and the small mounds of earth here are the slurry from puddling machines which flowed downhill to fill up the gully.

Stop 4

Remains of a puddling machine - technology to speed things up

To the left of the track is the remains of an 1870s puddling machine. Panning for gold is a slow process. To speed it up, diggers constructed circular ditches nearly a metre deep with an island in the middle. On the island was a pivot post that supported a long strong pole pulled around the edge of the ditch by a horse. Paddles or iron rakes hung from the pole to stir the soil and water into a slurry. When the slurry drained away, the miners could retrieve the heavy gold that had sunk to the bottom.

Stop 5

Coppiced Trees - surviving fire and felling

There is a clump of trees in a circle where the track divides here. Although they look like separate trees, they are actually multiple trunks of a single Red Ironbark (Eucalyptus sideroxylon), known as yeeripp by the Dja Dja Wurrung.

The tree probably began its life around 500 years ago, and originally had a trunk about one metre in diameter. Cut down near the base during the goldrush, the tree grew new shoots that developed into multiple trunks. This is known as 'coppicing' - a natural mechanism for eucalypts, enabling them to survive after fire.

Stop 6

The water race - and the race to end the drought

Droughts plagued the diggings, and sometimes work had to stop due to lack of water. This channel is part of a water race that was constructed in the 1860s and 1870s to bring water from the Coliban River. When water is released into the system (generally during summer) water appears in the channel here, as if by magic.

It is an incredible feat of engineering. The races are virtually flat, having a drop of only a few feet to the mile. No pumps are used - only the force of gravity allows water to flow gently downhill along the races. To achieve the very gradual slope and controlled flow required, the water races were constructed to wind around the sides of hills, following the contours. Where a steeper section was necessary, the race was lined and reinforced with stonework.

Stop 7

The school-teacher's and mine manager's house

This house was built in the late 1850s by a young English prospector who later became a school-teacher. The two-room stone cottage was described as having a "fine flagged floor and the best fire-place in all the Eureka".

When William Palliser moved to Castlemaine, his home was ideal for the manager of the Eureka Consolidated Company. Gold was precious, and security was always a concern. Living next to the tramway allowed him to keep a close eye on the company's gold!

Stop 8

Trolleys and tramways - smoothing the way

Alongside the mine manager's house was a tramway. Every day, trolleys moved tons of ore from the reef to the crushing plant. The wooden rails have rotted away, but the solid embankment remains. You can still see blocks of quartz on the ground nearby that may have fallen off an overloaded trolley.

Stop 9

The Eureka Consolidated Battery - crushing quartz into dust

Eureka Consolidated's quartz crushing plant operated here in the 1870s. Its foundations can be seen to the left of the track. A steam engine powered a series of pulleys and straps that operated twelve heavy iron hammers that crushed the quartz to dust to extract the gold. Day and night, six days a week, the sound of the battery's stampers would have echoed through the valley. The noise would have been deafening.

As you continue down the track, look for bricks from the boiler's chimney lying across the path.

If you only want a short walk, turn around here and take the short-cut between the house and the tramway back to the carpark.

Stop 10

The tailings - an enormous pile of dust

What happened to all the quartz dust from the Eureka Consolidated battery? If you stand near the fence here, you'll be standing on a huge pile of it! A wicker embankment (made of criss-crossed sticks and branches) at the narrowest point of the northern arm of Poverty Gully, trapped the tailings. However, the dam was breached long ago and most of the tailings have washed away.

Stop 11

The Eureka dam - no water, no life!

Water was crucial to life on the diggings, needed by the miners for survival, and also to separate gold from the rocks and soil. After the construction of the water races, water was supplied from the races to the dams. Each battery had its own dam - this one supplied the Eureka Consolidated Battery. Water was released to the crushing works by removing a plug from a hole in the dam wall. You can still see the fine stonework around this outlet.

Stop 12

The ridge - a recovering forest

Box-Ironbark forests once covered 13% of Victoria, but now only 17% of those original forests remain. During the gold rush, the trees at Eureka were felled for building and fuel, and hillsides like this were stripped bare. Remarkably, many native plants survived, and the forest is regenerating.

Eucalypts dominate the upper canopy, with many smaller species of trees and shrubs, like wattles, below. Common trees along the track here include the Long-leaf Box (Eucalyptus goniocalyx), Red Box (Eucalyptus polyanthemos), and Yellow Box (Eucalyptus melliodora).

In spring and summer, the forest floor is full of wildflowers, with species like Sticky Everlastings (Xerochrysum viscosum), Waxlip Orchids (Glossodia major), Leopard Orchids (Diuris pardina), Creamy Candles (Stackhousia monogyna), Pink Bells (Tetratheca ciliata), Black-anther Flax Lilies (Dianella revoluta), Chocolate Lilies (Athropodium strictum), Tall Bluebells (Wahlenbergia stricta), Magenta Stork's-bill (Pelargonium rodneyanum) and many others.

Yam Daisies (Microseris lanceolata), known as moonar to the Dja Dja Wurrung, have a small underground tuber which tastes like a sweet radish if eaten at the right time. The Dja Dja Wurrung People actively cultivated them as a food source. Their smooth leaves and bent-over flower buds help to distinguish them from similar plants.

The tussocks of fine grey-green grass here are Red-anther Wallaby Grass (Rytidosperma pallidum). It is one of many Australian plants that are stimulated to flower and seed after fire has passed through, displaying bright orange-red anthers in late spring or early summer.

Stop 13

Poverty Gully - looking back through history

Why name somewhere with so much gold 'Poverty Gully'?

It was probably named by early prospectors to discourage their rivals! The south arm of Poverty Gully is one of the most complex mining sites in the Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park. As the track continues up the gully, you can find the relics of several waves of mining spanning a century from the 1850s to the 1950s.

Stop 14

The cyanide tanks - a poisonous past

A cyanide plant was first established at Eureka during the 1890s to extract gold from the tailings of earlier diggings. It was reworked in the 1930s and 1950s when the tanks you can see were used.

Unfortunately, cyanide produces highly toxic mustard gas when combined with arsenic, which gold-bearing rock often contains. Mustard gas can cause severe burns, loss of eyesight, respiratory problems, rashes, blisters and extreme pain. It was used with devastating effects in World War I. To stop the gas from forming lime was added to the tanks. A small heap of this white clay-like material can be seen further along the track.

The tailings were soaked in the cyanide solution in sand-filled vats with a porous base. The dissolved gold passed through the porous base, while the tailings remained above it. This process took about 3 days, so filling the three tanks on consecutive days allowed the tailings to be processed continuously. The dissolved gold passed through charcoal or zinc shavings, forming a layer of slime which turned to liquid when heated in a furnace. It was poured into moulds where the gold reformed, leaving a layer of black glass-like waste on top which could be chipped off and discarded.

Stop 15

An earth-bound chimney - a cost-effective solution

This 'Cornish chimney' is one of the earliest quartz mining relics in Victoria. It dates from the late 1850s when the Phoenix Mining Company (also known as Blight's) battery operated in the gully below.

To avoid the cost and difficulty of building a tall chimney, Cornish miners built tunnels of bricks up the slope of a hill. The smoke drifted up inside the earth-bound chimney and emerged from a small upright section at the top. The small vents you can see were probably used for cleaning.

Stop 16

The Phoenix dam - being reclaimed by nature

This dam wall was probably constructed by the Phoenix Quartz Mining Company in the 1850s, before the system of water races was built, to catch rainwater flowing down the gully. The impressively-constructed stone retaining wall is still visible, but the dam itself has silted up.

Look on the slopes nearby for large Red Ironbark trees, with deeply rutted bark, which attract a wide variety of native birds, like the endangered Swift Parrot (Lathamus discolor).

Stop 17

A tall chimney - an expensive endeavour

This is the site of a battery owned by a Mr Harris. On the left of the track as you approach the viewing area, are the brickwork foundations of a blacksmith's workshop. Blacksmiths provided essential services to both miners and farmers - without them, work on the goldfields would have ground to a halt.

To the right of the viewing area are the remains of a vertical chimney, which was once 12m high. It cost 100 pounds to build - a huge sum of money in those days. The battery and stampers were in the gully below.

Stop 18

1930s stamping battery - a relic of the Great Depression

Eighty years after mining began at Eureka, a new battery was built here. In the economic depression of 1889 and the early 1890s, and the Great Depression of the 1930s, prospecting was more appealing than unemployment. Many mines were reopened, although few were profitable.

In the 1930s the sound of ten stamping heads would have echoed through this gully, supported by two blocks of concrete that formed the foundations.

Stop 19

Tunnels and bats - finding a niche below the reef

In the 1930s, this tunnel (known as an 'adit') was dug into the sandstone below Eureka Reef. About 150 metres in, a vertical shaft (a 'stope') was constructed, allowing the reef to be mined from below. To the left of the tunnel is another shaft and a headframe constructed in the 1950s. For safety, both are closed to visitors.

The tunnel is now a roosting site for the Common Bent-wing bat (Miniopterus schreibersii), a small insect-eating bat. The bats are sacred to the Dja Dja Wurrung People, who call them yaranmillawit.

Just beyond the tunnel and shaft, to the right of the track, is another section of the water race. There would once have been a wooden bridge (also known as a flume or aqueduct) here that carried water across the gully to the race on the southern side. This was later replaced by a 'siphon' (an underground pipe). There are no pumps involved - just clever engineering and the force of gravity.

Stop 20

The miner's house - a clue to life on the goldfields

The ruins here were once home to a miner, and possibly his family. They remind us of the simple life people lived on the goldfields. The house was about 3m x 2.5m with a chimney at one end - about the size of a bathroom in a modern home.

In 1857, there were around one hundred men and twenty or so families living at Eureka. Regular wages from the mining companies allowed them to build homes and keep food on the table.

Stop 21

The mine shaft - and multiple waves of mining

The Eureka Consolidated Company began a gold mining operation here in 1871. It continued for about seven years and extracted nearly 16,000 tonnes of ore, yielding 175 kilograms of gold (roughly the weight of two adult men). The concrete platform in the car park covers the shaft dug to get to the lower level of the reef, 150m below.

In the 1980s, the shaft was briefly reopened to extract quartz for crushing into chips for the tops of graves. You can still see fine chips of quartz on the ground around you.

There's a hole in the platform big enough to drop one inside. Listen carefully and you can hear how long it takes to reach the bottom.

Safety:

Eureka Reef was a heavily mined area and contains a variety of continuing hazards. We recommend that you stay on the path. In addition to uneven ground and shafts, mine tailings may contain the toxic residue of arsenic, mercury, and cyanide. Fortunately, they pose little risk if left undisturbed. If you wish to safely explore mining relics away from formed tracks, we recommend hiring an experienced guide. Enquire at the Castlemaine and Maldon Visitor Information Centres.

Mobile phone reception is patchy at Eureka, and signals often drop out, especially in the gullies. In case of an emergency, the best spots to try and make a call are on higher ground.

Access for Dogs:

Dogs are permitted on leash.

How to get there:

From Chewton head south along Eureka Street which crosses a bridge and becomes Dingo Park Road. Continue for about 2.4km and you will pass an intersection with Poverty Gully Res Track. Soon after the road splits where there is a "Eureka Reef" sign. The left split goes to Jirrahlinga Dingo Conservation & Wildlife Education Centre while the right split goes down a short distance to the Eureka Reef car park. All the roads are gravel in good condition suitable for 2WD cars.

Review:

This is a wonderful walk which explores interesting relics from the area's gold mining history. The walk is on a very well-defined gravel track with numbered marker poles at each point of interest.

At the car park there is a picnic table and information signs about the area.

Photos:

Location

Dingo Park Road, Chewton 3451 View Map

Web Links

→ www.parks.vic.gov.au/places-to-see/sites/eureka-reef

→ Eureka Reef Heritage Walk Notes (PDF)

→ castlemaineflora.org.au