Avoca Chinese Garden

Beautifully positioned overlooking the river flats, Avoca's Garden of Fire and Water is a delightful attraction which reflects the Chinese heritage within the region. The garden represents and acknowledges the important contribution of early Chinese immigrants to Avoca during the gold rush era of 1850-1870.

The traditional Chinese pavilion features metalwork illustrating fire and the local wetlands; the large boulders positioned within the garden represent the scenic mountains of the Pyrenees. The paths lead visitors on a journey through a mixture of carefully selected plants both of Australian and Chinese origin, unveiling unique features and the diverse history of the Pyrenees.

Hidden with this beautiful garden is naturally formed 'scholar rock' a rock of particular significance to those with an interest in Chinese History. Guided tours of Avoca's Garden of Fire and Water are available and provide an interesting insight into the strong relationship between the early Chinese settlers and the beautiful Pyrenees.

Talk a 1.4km stroll through the gardens and then enjoy a light jaunt around the River Precinct.

There are extensively detailed information signs in Cambridge Street, just outside the Chinese Gardens (next to some colourful artwork on the road).

The text of the signs is:

THE CHINESE IN AVOCA

Signs of life in the Avoca Cemetery

In 2005, on the far side of the Avoca cemetery, hidden amongst some broken pine trees and long grass, there was a small brick funerary burner traditionally used by Chinese people to burn paper representations of clothing, money, possessions to serve the deceased in their afterlife.

There were also a number of quite fragile looking grave markers, each inscribed in Chinese, each covered by a heavy metal grill.

The crude method used to protect them suggested that some of the grave markers had been destroyed, or stolen. Apart from this there was a curious silence about what must have been an important social contribution to this small former goldfields town in central Victoria.

Someone did mention that one part of the old saleyards on the floodplain - the section at the north end with the higher fencing for cattle - had been the first burial ground for Chinese people in the town but that the bodies had been exhumed - perhaps to be transferred to the cemetery, perhaps to be taken home to China for burial there.

In recent years the cemetery has been actively repaired and maintained by a group of townspeople and the Chinese section is now clearly visible, carefully planted out with Ginko and Crepe Myrtle trees. And there is a splendid large stone plaque, placed by the Chinese Memorial Foundation in 2012, honouring the Chinese contribution to Victorian society. Three busloads of Chinese people arrived to celebrate the installation of the stone. They shared a wonderful feast with local people then got back in their buses and headed back to Melbourne.

This raises more questions rather than provides answers. Are there still Chinese people in Avoca? What actually is their story?

The promise of gold

Some details are well known. For instance we know that most of the Chinese who came to Australia from the 1850s came because of the promise of gold.

Two items in particular usually appear in any description of early Avoca - its natural beauty, and the large representation of Chinese on its diggings. Most of those who could be found on Victorian goldfields came from 'Kwangtung' ... They brought a particular system of gold mining, known as 'paddocking'. Here, all the washdirt in a valley or gully was removed, washed for gold, and then replaced to leave the ground in a state as close as possible to the original. (From 'The Men From Kwangtung')

The walk from Robe

It is also widespread knowledge that, because of the Chinese Immigration Act, which included a tax on Chinese immigrants at Victoria ports, the boats that carried them first docked in Adelaide then later at the free wharf in Robe, South Australia and they were obliged to walk overland to the central Victorian diggings.

A traveller in 1854 described a group of Chinese he saw:

'...between six and seven hundred coming overland from Adelaide. They had four wagons carrying their sick, lame and provisions. They were all walking single file, each one with a pole and two baskets. They stretched for over two miles in procession. I was half an hour passing them...'

The Chinese in Avoca in 1868

In 1868 when much of the gold had gone from the area, in "Avoca: Statistics of Chinese Population, and particulars of their Employments" the Chinese Interpreter, How Qua, noted:

250 total population of Chinese

50 Chinese in the largest camp

150 Chinese married in China

4 Chinese married to European women in this colony

9 Chinese children; four go to school

218 Chinese are miners

2 puddling machines each employing six Chinese...

2 Chinese employed by Europeans at their claims

10 shopkeepers

10 market gardeners and sellers of vegetables

1 doctor

1 tailor

2 butchers

5 carpenters

1 cook-shop

6 unemployed Chinese

Future possibilities

The question remains. Where might the descendants of the Chinese people who lived in Avoca be now? And what might happen next now that we have this garden? The Garden of Fire and Water is, in a way, a gesture of support to the three busloads of Chinese people who drove into town and gifted us this plaque. Already many Chinese people are coming to Avoca or stepping forward for the official opening of this garden. And the children at the Primary School are learning Chinese.

A CONTEMPORARY CHINESE-AUSTRALIAN GARDEN

The Avoca Chinese garden was named the Garden of Fire and Water by Chinese / Australian artist Lindy Lee, the lead artist in its creation. She recognized that fire (as bushfire that leads to destruction but also to plant regeneration) and water (as rain or flood) are potent elements of the cycle of life in Australia.

She also knew that these are simultaneously powerful symbols of Chinese culture, present in the I Ching, (the Book of Changes / Book of the Oracle that led to both Taoist and Confusian philosophy. With its origin in 'mythical antiquity', it is still widely used as a book of wisdom that employs chance relationships through the throwing of coins or yarrow sticks). Thus the final hexagram (number 64) of the I Ching is called 'Before Completion'. In suggesting that 'completion' will never occur, that life is an on-going cycle, it's image is 'fire over water'.

Here, then, is a pavilion of fire (with charred posts, detailed decorative 'lacework' of burned metal and a roof profile of flames) actually providing water for a large pond below. This is supported with storm water from the street that is cleaned by the reeds in the pond then used in a gentle fountain or siphoned off, now clean, to the river.

The pavilion, with its turned-up roofline is a direct, easily recognized representation of China However the posts with which it is made, the iron on the roof (instead of the usual tiles), and its height can equally be seen to refer to the many hay sheds in the local surrounding countryside.

Similarly, the water element is a similar size to many of the dams in the area and the rocks can also be seen dotting the local wheat fields while the slate comes from Donkey Hill, nearby and is used throughout the town.

The garden is a contemporary Chinese garden in Australia. As such it represents the important contribution of Chinese people in the culture, those who came from China as immigrants and are now Australians and those Australians whose parents or grandparents came from China.

A brief history of the Chinese landscape garden

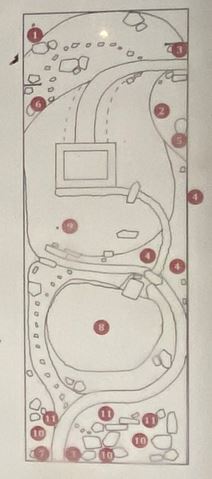

In the traditional Chinese 'scholars' garden (a smaller garden focusing on presenting a landscape in miniature), the central features, which are carefully placed to support their symbolic value as parts of the larger landscape, include:

Architectural structures

including pavilions, bridges, gates (especially round 'moon' gates), walls, all of which frame views as people move through or stand and look at the garden from different vantage points. In the Garden of Fire and Water, this aspect will increase as the plants grow to both hide and reveal various 'scenes'.

Rocks

often placed to present miniature mountain ranges or for singular contemplation (the 'scholar' rock) these 'symbolize the eternal' (yang). In the Avoca garden, the scholar rock is small, golden and hidden from first view.

Water

to present oceans and rivers. It symbolizes the ever-changing (yin).

Plants

that provide a focus on each of the seasons and, in relation to the history of landscape painting, hold specific symbolic resonances.

The borrowed landscape beyond

Importantly, the Scholar's gardens could never be seen from any one viewpoint. Equally importantly, they were extended past the bordering walls by 'borrowing' from the surrounding landscape. Views were framed to take in distant hills and vegetation.

The Garden of Fire and Water has taken this contextual relationship further. By siting it within the fencing of historic saleyards it actually allows the town to embrace the floodplain. And, instead of separating the garden from the life of the town with walls, the historic cultural complexity of the site is honoured, for it is nearby where many of the Chinese people of 1850's and 60's Avoca lived and were buried.

BUILDING THE GARDEN

About the selection of plants

This is a garden of a number of symbolic Chinese plants within a 'borrowed' Australian landscape.

Many of these Chinese plants have already migrated and happily settled in Australian gardens. Several have been selected primarily because they already grow well in the town.

This story of plant 'migration' is seen across the world. Different varieties of the Pomegranate and the lotus, for instance, are ubiquitous across central Asia. Others, like the flowering quince ('Japonica') and the 'Mt Fuji' cherries we have planted are now more closely identified with Japan although their origin was China.

Our selection has been made on the basis of soil type (strongly alkaline), climate (heavy winter frosts and long, hot, dry summers), on not attracting possums (as with fruit trees) but encouraging birds. As part of the garden sits on a flood plain, this lower area is planted mainly with River Red Gums and grasses that happily survive inundation. Most importantly, the symbolic Chinese plants have been selected to provide colour across the seasons, of central importance in traditional Chinese gardens.

Chinese plants

1. Pomelo, an ancestor of the grapefruit, its presence for New Year expresses the wish that the home will have everything it needs in the coming year. Gift from Mr Russel Jack and the Golden Dragon Museum, Bendigo.

Winter colour

Nandina domestica (Sacred Bamboo) berries in late winter, symbolizes endurance.

2. Chaenomeles double red (Flowering quince).

Spring colour

3. Wisteria sinesis (Wisteria) with mauve flowers.

4. Prunus serrulate 'Mt Fuji' (Flowering cherry) with white blossom, it represents 'creative power and purity amid adverse surroundings'.

5. Paeony with bright pink double blooms, it is a symbol of spring, representing beauty, rank, higher social status, luxury, opulence.

Summer colour

6. Bamboo youth, suppleness, strength endurance flexibility longevity (also the symbol of summer)

7. Punica granatum (pomegranate) represents fertility, called '100 sons fruit'. Suggested by Melbourne Botanic Gardens.

8. Nelembium nucifera (Lotus) represents ultimate purity and perfection because it rises 'untainted and beautiful from the mud'. Medicinal properties.

Hemerocallis (Day lily) represents filial devotion to one's mother and wealth.

Autumn colour

9. Ginko Bilboa (Maidenhair tree). Gold leaves in Autumn. The nuts represent hope for silver, wealth. It has important medicinal properties.

Prunus serrulata 'Mt Fuji' (flowering cherry). Red leaves in Autumn.

Australian plants

10. Eucalyptus Camaldulensis (River red gum).

11. Xanthorrhoea australis and Xanthorrhoea minor (grass trees)

Other grasses and ground covers include:

Anigozanthos flavidus green (tall green Kangaroo Paw)

Carex appressa (tall sedge)

Carex fasicularis (Tassel Sedge)

Baumea articulate (jointed twig rush)

Dianella caerulea (blue flax lily)

Eleocharis sphacelata (Tall Spike Rush)

Erimophila debilis (winter apple)

Gahnia sieberiana (red-fruit saw edge)

Juncus holoshoenus (joint leaf rush)

Poa labillardierii (common tussock grass)

Photos:

Location

Cambridge Street, Avoca 3467 View Map

Web Links

→ Avoca Chinese Garden River Walk (Walking Maps)

→ Avoca Chinese Garden Small Town Transformation on Facebook